Karen Stander & Annette Holtkamp

Immersing ourselves in the Bodhi Khaya forest led us to relinquish control and work with a more instinctive, child-minded openness. The residency became a three-way collaboration – between the land and the two of us – guided by spontaneity, curiosity, and playful dialogue.

We responded to what the environment offered: fibres, wind, shifting light, and the lines and gestures of branches and roots. A looped branch suggested weaving into it with forest fibres; the form of a wild bible plant prompted us to echo it using leftover papadams from the kitchen. Our process became a cycle: listening with all senses, gathering, making, and letting go – guided by a commitment to do no damage.

Rather than working from intention, we interacted with the site’s rhythms, attentive to slow transformations through sun, wind, rain, and animals. Many works blended so closely into the surroundings they felt grown rather than made. They were not displayed but waiting to be discovered, shifting in light and breeze, and ultimately returning to the soil. At times we introduced surprising humorous notes – such as hanging masks made from pear slices or leaves among the trees – that invited viewers to question what belonged and what was imagined

Katleho Habi

First encountered, the nature of Bodhi Khaya felt like a deep inhale, a deep breath that could only be exhaled through frequency — words ultimately failed me. Bodhi Khaya, while vividly reminiscent of the ancient, preserved land in my home of Lesotho, presented me with an impulse for insisting on newness. It felt wildly beautiful and wildly unfamiliar…in need of an honest speaking back on its history, its sociopolitical implications, its threshold, its imminent movement towards a renewal that would be marked by a fire the day before we left.

It was itself: the botany, mountains and water held a deep knowing, of which I became fractionally familiar within the two weeks I spent in the forest…a reverberating studio unafraid of time or place.

Luke Rudman

Time at Bodhi Khaya moved differently. Sharing space with other artists and thinker, as well as with the owls and baboons and trees and lichens – all on their own missions of survival and creativity. My time at Bodhi Khaya facilitated a magical, deepened understanding my work and body in relation to the non-human world.

At first, I came in with a very specific idea of what I wanted to do during my time at Bodhi Khaya – but I soon realized that this wasn’t the place for business-as-usual. As a drag performer, I arrived at bodhi khaya with rhinestones, pink thigh-high boots and boxes of costumes and body-paint. The more I engaged with drag at Bodhi Khaya the more I started to recognize myself in the landscape and its inhabitants. The surreal, vibrant moths with their feathery eyelashes looked just as painted as me. The flowers bloomed so brightly with saturation that challenged even my most neon eyeshadows. The flamboyance of birds and the iridescence of insects embodied drag’s defiance of the dull and the rational. They both use spectacle not for vanity, but as strategy, seduction, and self-preservation. This residency set the scene for me to start to understand the ways in which my drag is an act of protection, healing and self-preservation too. Who am I to assume how flamboyant, colourful moth feels when I stare at it? – maybe it feels the same way I feel when I am painted.

Luke Rudman

Carin Bester

At Bodhi Khaya I entered into dialogue with the land through silent movement, and repetition. It started with long walks and time spent alone listening. From the start I was drawn to the spiral pattern of the snail shells seen in the forest and particularly the whiteness of their decay and I think as with many artists at the residency I was drawn to the clay from the quarry and their colours and how one could reflect the natural world when covered in the clay. White clay for calling, yellow for renewal, red for the pulse of the feminine. The continues presence of raptors in the sky, guided me in ways still unknown. It was felt without words to describe.

Kringloop van Stilte was a twelve-hour offering, I worked in slow repetitive circles of clay and stone, tracing a spiral that grew smaller through the day, an act of becoming less / taking less space, so that the land could be more. Each movement was both offering and grief. Through washing and applying clay, I sought to meet the land not as visitor but as element, blurring the line between body and ground, between breath and dust to become part of what I was tending. Dust to Dust.

As the final offering I planted my hessian dress sewn with seeds gathered on my walks, an act of giving back what was held. The performance lived between ritual and meditation, between breath and soil. It was not about spectacle, but about presence. About how tending, slowly and without speech, might begin to answer the question of how we can heal.

Carin Bester

Jenny Nijenhuis

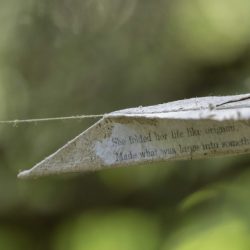

Resonance Swarm is an installation of paper planes and drones made from mushroom pulp and bound onsite using handmade fiber thread. These materials, foraged in the forest at Bodhi Khaya, will eventually return to the earth.

The paper planes represent prayers, drawing on the Japanese tradition of tying written prayers to shrine branches to invite healing and release hurt. I bound the planes into the branches and root structure of a 500+ year-old Milkwood tree, forming a swarm. Four mushroom-pulp drones hover ahead, oriented toward the swarm to generate a palpable tension.

By using foraged mushrooms to construct the suspended installation, I aim to invoke the intricate mycelial network – delicate, threadlike filaments of the unseen underground web that sustains the larger fungal organism. Mycelium connects individual plants, facilitating the transfer of water, nitrogen, carbon, and other nutrients, while reliably transmitting signals across the same frequency range. Old-growth forests possess resilient, balanced energy fields, with trees harmoniously linking what exists above the ground to what lies beneath.

Jenny Nijenhuis

Karin Slater

Forest Beings – An exploration of presence, process and performance in virtual space.

A VR film series with Katleho Habi, Carin Bester & Luke Rudman

My time at Bodhi Khaya Artists Residency was deeply meaningful. I arrived intending to focus solely on a long-term film project, “Waiting for Evolution” about the complex and often painful relationship between baboons and humans in the city of Cape Town. Having the space, time and support to work allowed me to make tremendous progress on the film. Stepping away from the intensity of the situation, gave me a fresh perspective on the kind of film I want to make and why it matters.

While at Bodhi Khaya, I found myself drawn to the work of the performance artists on the residency, Katleho Habi, Carin Bester and Luke Rudman. I was inspired by their courage to share their vulnerability while finding ways of embodying emotions and expressing their relationships to the natural world. This inspiration sparked an unexpected creative expansion. I began making a series of three short Virtual Reality films each from the perspective of a forest being that held significance for the performance artists. These VR works, The Moth, The River and The Sparrow Hawk, explore connection and transformation between human and non-human worlds.

To showcase the work, I set up a virtual reality experience in the forest. It included a headset, a small waiting area and a whiskey tasting. A playful, immersive way to invite people into the environment I love most: nature. Although the rain drove us into the barn, the experiment was inspiring. It opened up new possibilities for my practice. It showed me how it’s possible to transport people into natural spaces, both physically and through a Virtual Reality film experience.

Silindokuhle Shandu

My time at the Bodhi Khaya residency was a mix of beauty, stillness, and quiet reflection. The landscape and creative atmosphere encouraged me to expand my expression and begin developing a new style in my work.

Being in communion with other artists, sharing ideas, processes, and silence was incredibly enriching, and I’m sure this experience will continue to inform my practice in the future.

The residency made me think deeply about land, access, and belonging, with curiosity and awareness. It is an experience I’m grateful for one that has shifted something in me creatively and personally.

Silindokuhle Shandu

Marisa Maré

In my process-based practice, I explore the interplay between making and unmaking through the use of bioplastic, an ephemeral material that returns to the Earth. During the residency, I set up a make-shift lab to produce sheets of bioplastic for an installation in the forest. I worked with local plant material, including yellow Helichrysum flowers and Usnea lichen, to create inks and pigments. These natural sources surprised me with their range of colours. The lichen produced a vivid orange, while the young Helichrysum flowers created a translucent yellow once I adjusted the pH of the bioplastic solution. Clay from the area provided rich earth pigments in tones of red, yellow and sage green.

A walk through the forest on the first day led me to a semicircular structure of knotted vines that rose from the soil in a semicircular form. I began placing pieces of bioplastic in the spaces between the vines, using biodegradable flax thread to attach them. The slow process helped me attune to the forest’s rhythms and presence.

Considering the shifting light on the work, I visited the installation both by day and at night. Titled As Above, So Below, the piece has been described as a kind of forest cathedral, offering a quiet moment of reflection and a sense of hope.

Documentation: Alisa Farr, Josie Borain, Bronwen Trupp, Karin Slater, Claire Gunn